Underbites are an undesirable dental feature that can cause a multitude of issues. Most notably, they can result in the patient being self-conscious of their teeth and as a result not smiling as frequently.

What can make matters worse is that underbites may be visible even when you are not smiling, as they can be the result of skeletal (bone) issues with your jaw structure. People who have

Fortunately, there are ways that you can treat underbites. See here for more information and for the most comprehensive guide currently available online, and how we can treat underbites at Marylebone Smile Clinic. Our clinic is one of the few clinics providing veneers for underbites, and we have been independently assessed and accredited in cosmetic dentistry.

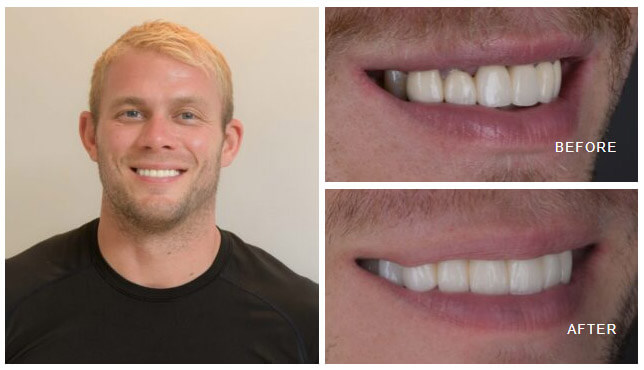

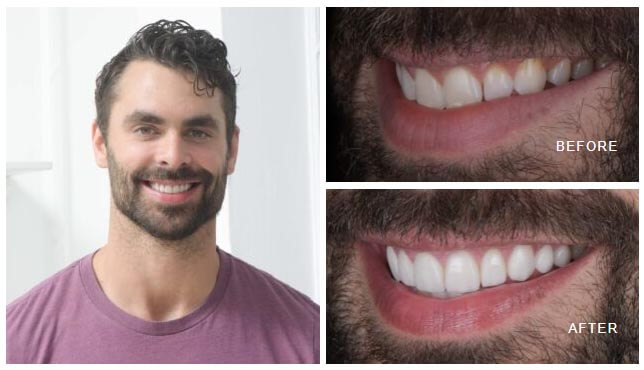

Here are some photos of our incredibly happy clients showing off their stunning dental veneers:

FAQs

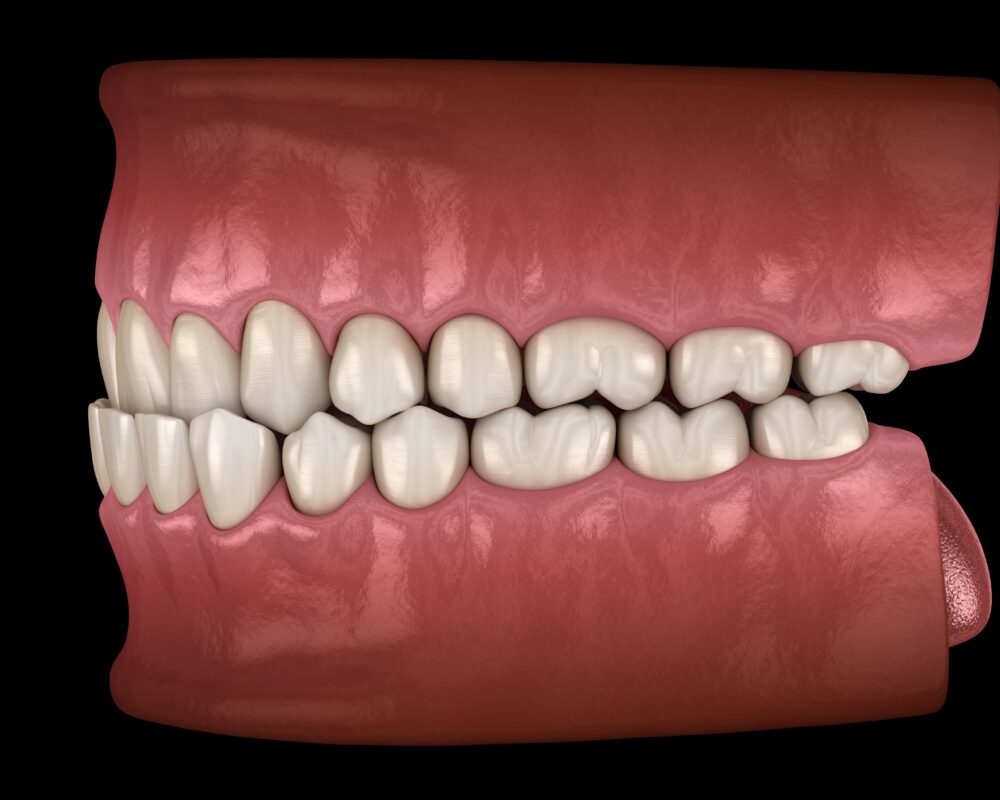

What is an underbite?

An underbite is an increasingly common term used for where the top teeth do not overlap the bottom teeth, or they are in a reversed position.

Underbites are not just problematic aesthetically, but also practically and functionally too. If you have an underbite, your ability to bite and chew food will be affected. And on top of this, you can be more prone to tooth decay, sleep breathing disorders (SBD), and some issues with your speech.

The common approaches to fix underbites are braces with surgery and in modern times, ceramics/veneers. In the case of veneers, in order to correct an underbite, often top and bottom teeth need to be treated simultaneously to develop a new bite position. Have a look at our bite correction gallery for some examples.

What causes an underbite?

The most common cause is a mismatch in size of the top and bottom jaws, in their position and growth pattern. Ideally, we prefer the top jaw to be slightly larger than the lower, and in the case of underbites, the bottom jaw is significantly larger than the top. This causes crowding and malposition of teeth through adolescence, aesthetic issues and an extreme jawline. This can appear excessively strong, masculine or aggressive.

Can you fix an underbite?

Underbite correction is possible using a few different treatments. The most common methods are braces and surgery. However, porcelain veneers for underbites are also an effective treatment that also addresses tooth colour and shape simultaneously.

If you attend a consultation with a dentist or cosmetic dentist, they will be able to identify the cause of your underbite and decide on the most appropriate mode of treatment to get you the best results.

Also, it is important to note that the best time for a patient to receive treatment for their underbite is when they have completed their growth of their jaws, which concludes aged 21. Whilst it may be possible to prevent an underbite from getting worse at an earlier stage, comprehensive treatments at adult age are almost always the only method to definitely fix an underbite.

How to fix an underbite

How your underbite is fixed will depend on how your underbite is caused.

Braces are the primary option used in NHS hospitals and are also sometimes used in conjunction with surgery to achieve results for patients with severe underbites. Orthodontic treatments are capable of changing the position of the teeth dramatically over a period of time, although it is this long period (2-3 years) of time that is off-putting for a great number of patients.

If your underbite is minimal, moderate or severe, you may be able to receive veneers for your underbite. This will depend on the degree of bone related discrepancy and the relative tooth positions. Increasingly, with modern ceramics and digital planning tools, we are able to correct up to a moderate-severe underbite without braces. This will be a much quicker fix than if you were to receive braces, and will also provide other aesthetic benefits such as tooth colour and tooth shape.

In the case of ceramics, used to correct an underbite, usually the top and bottom teeth need to be treated simultaneously. This is to redesign an ideal relationship between the upper and lower teeth by changing how they interact in your new bite. If you only treat one set, then you may run the risk of untreated teeth damaging the veneers.

Veneers for Underbite Correction in London

Veneer teeth are highly recommended if you are eligible to receive them. They are reliable, long-lasting (15-20 years), and capable of giving you the perfect smile by hiding a number of aesthetic problems such as worn-down teeth, tooth gaps, and teeth affected by underbites. Due to the relative lack of Accredited cosmetic dentists in the UK providing underbite correction, we advise searching for clinics that manage the condition frequently and are experienced in the field.

For more information on how we can help you if you have an underbite, then get in touch with us at Marylebone Smile Clinic and we can schedule a quick chat or a consultation.

You may be able to fix an underbite without braces if you receive surgery, veneers, or clear aligners such as Invisalign.

If you are a child and you have spotted an underbite developing at an early stage, then you may be able to use a number of tools to treat your underbite while your jaw bones are more malleable than those of an adult.

You can find out more about our veneers at our veneers London page.

Will Invisalign fix an underbite?

Invisalign or clear aligners is typically not a good option for an underbite, due top the reduced control with clear aligners. Fixed or train track braces provide more control to the tooth movements required and in the case of an underbite, a high level of control is needed.

Do I have an underbite?

If your lower teeth come out further than your upper teeth and overlap them, then you have an underbite.

This is different to an overbite which is when the upper teeth come over further than the lower teeth and overlap them by an extreme ratio.

Is it bad to have an underbite?

Yes, it is bad to have an underbite because it can lead to a number of issues such as tooth decay, gum issues, pain, and problems eating, and aesthetics.

An underbite is generally the more severe problem when compared to overbite teeth, because people should have some level of an overbite and overbites are easier to treat with various treatments.

How to fix an underbite without braces?

The essence is that we modify the bite by raising and repositioning the bite forces such that the teeth can be aesthetically and functionally in different positions. This requires careful and specialist planning, involving a test phase on models, following by a temporary veneer phase and then converted into ceramic once all parameters are met. Typically the process takes place over 4 appointments over an 8 week period.

Can I get veneers with an underbite?

Yes, you may be able to receive veneers if your underbite is minimal, moderate or severe and this depends specifically yon your current situation. An in-depth assessment with an Accredited cosmetic dentist is a good first step in your research.

Underbite Correction: A Technical Roadmap

Please be aware the following is a detailed description, which includes a thorough explanation of the techniques used to correct underbites with veneers.

The orthodontic approach to correct underbites is well documented, and although it is not the subject of this report, it was presented as the classical and generally accepted route to improve malocclusions. It is accepted that restorative approaches to underbite and occlusal rehabilitation have a weak evidence base, possibly due to the low number of cases being treated and the difficulty in data collection and post-operative analysis. In the absence of a reliable peer-reviewed evidence base, sound biomechanical principles coupled with an intricate working knowledge of occlusal parameters are the foundations of this technique. Whilst the treatment to restoratively correct an underbite case present a biological risk, in accordance with the client’s values and aims, it is an acceptable approach if it is the only agreeable option in the patient’s opinion. A purely restorative approach is complicated by there being an asymmetric spread of space through acquired tooth loss, potentially limiting ideal proportions (Magne 2003). Further, the compensatory effects over the life course limit the gingival harmony possible.

Underbite Management and Intervention

The principles in occlusal rehabilitation remain as establishing a joint based occlusion that is respectful of the patients adapted guidance envelope as well as the condylar pathway (Piper). The first point in planning is determining if the case requires mounting at the current condylar axis, or at another point, either centric relation or another orthopaedically stable position. A joint based occlusion is the teeth relationship being influenced by the joint position, and this case the skeletal discrepancies and hypodontia caused crowding and crossbites which in turn creates asymmetric wear as an adaptive mechanism.

The models were articulated on a semi-adjustable articulator, with the condylar pathway set with average values initially. The composite resin bite registrations were used to define the intended centric relation or airway centric relation position. Once the casts were locked in this position, the diagnostic wax-up could begin. First, the VDO is raised by 4-5mm+, such that the new occlusal scheme will permit the upper arch to be brought into a positive overbite. In order to achieve this, the lower arch model required lingualisation (reductions) and the upper arch model buccalisation (additions). The extent is firstly judged by achieving a positive overbite and secondly balancing with the contralateral side in buccal volume. Close communication between clinician and ceramist is required to ensure the aesthetic and biological parameters of the case are met concurrently with the functional aspects. In raising the facial vertical dimension significantly, the findings of Tallgren (1957) supported that some increase in facial vertical dimension occurs over the life course, which may indicate the use of VDO increases in active dental treatments could be tolerated.

The subsequent stages of the wax-up was to test new guidance pathways. Pre-operatively the patient was in an established reduced overbite (underbite) and reverse overjet, and anecdotally class III patients often have wider guidance envelopes. Diverting the case into a class I incisor relationship may encourage parafunction due to it steepening his adapted movement pattern. The risks relate to chipping, breakage, pocketing, discomfort and longer term abfraction defects. This was considered in detail before opting for group function in order to provide stable platforms for new guidance pathways. The verticality of occlusal forces are spread from 7-5s, with lighter contact across the 4-1s. This typically does not cause the intrusive effects that would negatively impact a definitive restoration. The typical movements observed for previous cases were extrusion of the 7s.

Preparation and Occlusal Test

In transferring and adjusting a new occlusal scheme, the collaboration between the clinician and patient is critical to finding the new occlusal pattern that satisfy the various demands of the case. Specifically, comfort in function, aesthetically pleasing, force distribution within acceptable limits, no evidence of fremitus and acceptable stress on temporary bisacrylic resin restorations (Seay 2014). In order to provide elective treatment, a broad understanding of material properties and biological parameters is paramount. In the current climate of reducing intervention, it is the authors ideal to solve aesthetic issues in a preservative manner that mitigates the long-term risk for the patient. To this end, restorative preparation is performed with close reference to the reductions made on the diagnostic models. Buccalisation of the upper arch required reductions relating to the transposition of the canines as laterals and premolars as canines. This increased the need for undercut removal to give the ceramist the space to form new anatomy over the abutment. Lingualisation of the lower arch presented the highest requirement for precision, due to the need for tooth structure preservation and the desired occlusal outcomes. The final feature of the preparation stage was undercut removal, which allows the technician to conceal the margins within deflective areas.

Technical Step: Alveolar Models and Frameworks

Alveolar models are occasionally referred to as Geller or Carrot models, and are a powerful aid to visualise the soft tissue during aesthetic ceramic builds, optimising emergence and soft tissue control. Firstly, the impression was cast into a solid model. The prosthetic margins were delineated and the subgingival profile was trimmed into a conical or ‘carrot’ shape. The abutments were placed accurately into the original impression and blocked with a cyanoacrylate and wax. The boxed impression is then re-cast and finished in order to show removable dies within a solid model. The single dies, solid model, and provisional model were digitally scanned and overlaid to ensure space parameters were respected, and the frames were milled from wax and examined under a microscope. All units are pressed in a lithium disilicate following investment and burnout at 850°C for 60 minutes. They were divested, the reaction layer removed, and frameworks fitted down in a controlled stepwise manner, to avoid marginal fracture. The fit of the frames was finally confirmed on the alveolar model prior to ceramic layering.

Several bite registration methods exist, and the authors’ inclination is to record an occlusal registration jig in airway centric relation prior to administration of anaesthetic and sedation. The left-hand side (LHS) was prepared first and occlusal registration taken with the pre-operative registration in place on the right-hand side (RHS) to serve as a verification tool. The inverse of this process is repeated once the RHS is prepared. Each instance when the patient is asked to occlude their teeth incurs a possibility that the position differs to the target end-point. If the change is not detected by the clinician, positive or negative errors can be significant during the technical ceramics phase. Alternating verification jigs reduces the risk of positive and negative error. If there is any unilateral inaccuracy, the alternating rhythm of registrations was repeated to sequentially increase the accuracy of each new jig. In readiness for each occlusal registration, the anaesthetist was requested to reduce the active dose of sedative, in order to temporarily bring the patient out of deep sedation to improve responsiveness. Furthermore, a digital occlusal scan was taken as a secondary measure to reconcile against errors in the analogue process. A fast-setting rigid vinylpolysiloxane (VPS) was used throughout and the most accurate versions labelled and stored in rigid containers.

Technical Step: Porcelain Build

- Liner: Glaze paste is used in combination with internal staining to increase value and provide micromechanical texture to bond the subsequent porcelain. Fired at 770°C for 30 seconds.

- Dentine-Enamel: Control of chroma and brightness was performed with B1-B0 dentines and enamel transpa neutrals. Fired at 780°C for 60 seconds.

- Effects: Various effect porcelains were combined to increase fluorescence and realism with interaction in different colour temperatures. E57 enamels, PSO effect and transpa neutral were the author’s preference in achieving natural shades such as BL4. According to the shade map and clinical photos, pink porcelain was combines between three manufacturers to provide the adequate shading whilst respecting the coefficient of thermal expansion parameters. Fired at 770°C for 60 seconds.

- Glaze: Glaze paste was thinned to 50% consistency and used across the entire surface. Fired at 765°C for 30 seconds.

Upon cooling, the restorations are hand polished, including almost complete removal of glaze from the occlusal surfaces. They were verified against an incisal transfer matrix of the approved provisionals and adjustments were made where necessary in collaboration with input from the clinician. The intaglio surfaces were steam cleaned, etched for 60 seconds with a 9% hydrofluoric acid, washed and dried.

Operative Step: Insertion

The bisacrylic resin provisional crowns and veneers were removed via torsional stressing, and the abutments were mechanically cleaned with hand and ultrasonic scalers. A transparent water based try-in paste was used to ascertain accurate fit, proximal contacts, colour integration, as well as to reaffirm the aesthetics to the patient. On approval, intaglio surfaces were cleaned with a 37.5% phosphoric acid to remove saliva borne contaminants. A two-bottle silane was applied to all restorations and air dried. Partial coverage abutments were isolated and treated with phosphoric acid for 40 seconds, a two-step etch-rinse bonding system, followed by the corresponding white resin cement. Full coverage abutments were cemented in sectional quadrants in a stepwise method with a resin modified GIC, loaded minimally from margin to base. The accurate and positive seating of the restorations was confirmed multiple times through firm apico-buccal pressure with three phases of tack curing. Excess cement was removed with a No.12D surgical blade, hand scalers and dental floss. Post-operative radiographs were taken to detect residual excess cement. Occlusal parameters were initially assessed with petroleum jelly lined 40 micron articulating paper in MIP (blue), and in all excursions (red). The priority was to avoid introducing additional interferences or steepening of existing posterior guidance. It is advisable to reduce interferences as per Albert Solnit’s selective grinding sequence, redeveloped by Lane Ochi. Adjustments were made with fine convex diamonds and polished with two grades of polishers. Excessive loading of the ceramic-tooth interface is controlled in this way, which was reconfirmed at the review appointment. Removable retainers were issued as a protective and retentive measure.